[/quote]

Somali state security forces forcibly evicted about 21,000 displaced people in the capital, Mogadishu, in early March 2015. The authorities beat some of those evicted on March 4 and 5, destroyed their shelters, and left them without water, food, or other assistance. Many of those affected had fled their homes during the 2011 famine and fighting, and have been repeatedly displaced since then.

Somali authorities should cease forcibly evicting displaced people in Mogadishu, and adequately protect and assist them, Human Rights Watch said.

“The Somali government has done next to nothing over the last three years to address the miserable and unsafe living conditions for Mogadishu’s thousands of displaced people,” said Leslie Lefkow, deputy Africa director at Human Rights Watch. “Now, instead of providing safe alternative options and much-needed water and sanitation, security forces are violently uprooting them, leaving them homeless and destitute.”

Human Rights Watch spoke with 17 camp residents and 6 other witnesses to the March evictions and analyzed satellite imagery of the area recorded between February 27 and April 9. From March 4 to 7, Somalia’s national police, national intelligence agency forces, and city council police forcibly evicted the thousands of internally displaced people from informal camps in the Kahda (formerly Dharkenley) district in Mogadishu. During the operation, security forces beat those resisting orders to vacate, destroyed shelters and shops with their hands and a bulldozer, and threatened displaced people.

Authorities failed to provide adequate notification and compensation to the communities facing eviction, and did not provide viable relocation or local integration options required by international law, Human Rights Watch said.

Aid organizations estimate that 1.1 million people throughout Somalia are displaced, including an estimated 370,000 in Mogadishu. Precise data is not available because the government has not officially registered displaced people. Since 2011, women, men, and children living in informal camps for the displaced have beensubjected to serious abuses including rape, physical attacks, restrictions on access to humanitarian assistance, and clan-based discrimination at the hands of government forces and affiliated militia, as well as private parties.

According to the United Nations refugee agency, UNHCR, at least 25,700 people were forcibly evicted in the two months prior to the Kahda operation. However, the Kahda eviction was particularly brutal, Human Rights Watch said.

IDP camp Mogadishu

![]()

![]()

Human Rights Watch obtained a copy of a February 25, 2015 notice from the Benadir Regional Administration signed by the mayor of Mogadishu. It stated that people living in a specific 600-by-650-meter section of “government land” should vacate within a week and ordered the local district commissioner to inform affected communities.

Residents told Human Rights Watch that many did not receive the notice or any notification from the commissioner. Several first learned of the impending operation about three days before it began, when security forces arrived in the camps and painted the word “demolish” (dumis in Somali language) on some shops bordering the main road. No one interviewed had seen the official written order, and most had been unaware of the planned evictions.

Several camp residents said security forces beat them when they refused to vacate or dismantle their shelters on March 4.

A 33-year-old mother of seven told Human Rights Watch:

There were three gunmen. One shook my hut and I tried to stop him because my baby was inside. He slapped me, but I cried and shouted, “My daughter is inside! My daughter is inside!” He finally stopped shaking the house and told me to take my daughter. As soon as I got her, he uprooted the sticks holding up our shelter, it collapsed, and he moved on to destroy the one next to mine.

Governments may lawfully evict people under exceptional circumstances, such as for the public interest. However, to be lawful, evictions must be carried out in accordance with both domestic and international human rights law, including with proper notification and other due process protections. Displaced people who are moved from where they are living must be given alternative housing and access to food, education, health care, employment, and other livelihood opportunities.

The Somali government has adopted a policy on displacement that spells out clear procedures aimed at protecting affected communities during evictions and ensuring that evictions are lawful, but has failed to observe them, Human Rights Watch said.

“At every turn of these operations, the authorities violated their own policies on evictions,” Lefkow said. “If the Somali authorities need to move displaced people, the local and federal authorities in Mogadishu should first put in place a plan that ensures people’s security and access to basic assistance.”

Those evicted told Human Rights Watch that they had relocated further north into an area known as the “Afgooye corridor,” a stretch of road between Mogadishu and the town of Afgooye. They said, though, that they lack access to clean water and sanitary facilities, raised health and security concerns, and said they would probably move again.

Security is a serious concern along the Afgooye corridor, with ongoing attacks by the armed Islamist group Al-Shabaab against government and African Union forces. One UN official told Human Rights Watch that the agency’s staff is reluctant to visit and monitor some of the more distant areas where the evictees are living due to insecurity.

“Forcibly evicting the displaced to insecure areas without protection and with limited assistance puts them at tremendous risk,” Lefkow said. “All concerned, including the government, donors, and aid agencies, should make sure any evictions fully respect the rights of displaced people before, during, and after any operations.”

For further accounts of the March evictions, please see below.

The March Evictions

People who had been living in informal camps between the Aslubta and Sarkusta areas of Kahda district (formerly in Dharkenley district) on Mogadishu’s western outskirts told Human Rights Watch that in the early hours of March 4, 2015, members of the Somali police, intelligence agency forces, and city council police surrounded the camps. Some people reported hearing gunfire for several minutes and security forces shouting at them to vacate immediately.

Security forces started to evict residents from the camp shortly after the Morning Prayer, at about 4:30 a.m., beginning by demolishing shelters closest to the main road. They destroyed shelters and shops manually and with at least one bulldozer, and forced camp residents to dismantle their own shelters, often at gunpoint.

Evictees living further away from the main road said they were able to collect and take parts of their shelters and belongings with them. Others said they fled with almost nothing and lost their main means of survival. A 45-year-old man whose kiosk was along the main road said:

When I saw that the bulldozer was heartlessly destroying the shops around, I dared to take some of my goods. I said to myself, let them kill me, and I took some of the goods and parts of the roof. The bulldozer first hit its blade on the kiosk, and when the kiosk collapsed the driver drove over it one time and left it, and he started doing the same to the neighboring kiosks and everything in the kiosks was buried.

Aid workers told Human Rights Watch that the sanitation and water facilities at the camps were also destroyed.

While the bulk of the evictions occurred on March 4, the security forces patrolled the camps until March 7 and restricted access to some of those trying to return to retrieve their belongings. A displaced community leader who visited the eviction site a month later said that several displaced people’s camps in the vicinity had not been vacated.

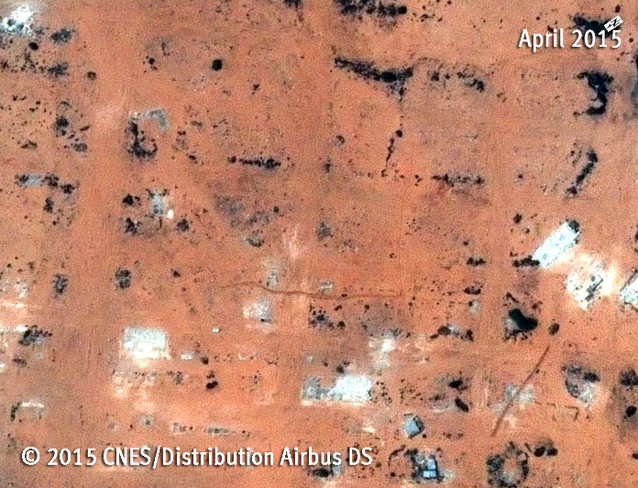

Human Rights Watch analyzed satellite imagery recorded on the mornings of February 27 and March 6, confirming that a large internally displaced persons (IDP) camp along the west side of the Afgooye road, immediately north of the Aslubta compound, was closed during this period and that over 3,400 family tents and associated residential and commercial structures had been removed from the site.

The satellite imagery also provided evidence that approximately 150 permanent buildings had been systematically demolished. The buildings probably had been used by international and local agencies to provide aid and basic services. The satellite imagery recorded on April 6 shows that over 1,000 additional IDP tents and related structures had been cleared after March 6 from three smaller camp sites within 300 meters of the original camp, raising the total number of removed or destroyed structures to at least 4,500 over a 5-week period. Human Rights Watch also identified evidence of continuing demolition consistent with the use of bulldozers and other heavy machinery to destroy the remaining permanent buildings as well as extensive tree cover in the area.

The imagery recorded also shows that several large settlements for displaced people were established approximately three kilometers from the eviction site sometime between March 6 and April 9, in an area known as “Waydow.”

A humanitarian assessment carried out in the aftermath of the eviction found that the majority of the displaced had no access to clean water and sanitary facilities, and just under half of those interviewed had no shelter. The assessment identified evictees over a 9-kilometer stretch of land, north of the eviction site.

None of the displaced people interviewed reported receiving any alternative shelter, land or assistance from the authorities prior to or since the March displacement. Many said they had previously been forcibly evicted from areas in central Mogadishu at least once, and most on several occasions, since they fled to the capital in 2011. According to UNHCR, in 2014 about 32,500 people were forcibly evicted, the majority from camps in the central Mogadishu districts of Hodan and Daynile.

Several displaced people told Human Rights Watch that they had lost their sole means of survival as a result of the latest eviction – some had lost their shops and others said the displacement had cut them off from day labor opportunities in town.

Human Rights Watch has reported on a range of abuses against displaced communities in Somalia. Human Rights Watch also found that limited livelihood opportunities put displaced women and girls at particular at risk of sexual violence and exploitation – including by forcing them to undertake long and often hazardous journeys to collect firewood, to secure day labor, or to beg.

Applicable Standards and Policies During Evictions of Displaced

Under international human rights law and the African Union’s Kampala Convention on the Protection and Assistance of Internally Displaced Persons (the “Kampala Convention”), the government has the responsibility to respect the human rights of the displaced without discrimination. Somalia has ratified the Kampala Convention – the first regional instrument aimed specifically at preventing displacement, protecting and assisting the displaced, and identifying durable solutions – but not yet deposited the instruments with the African Union. However, under the Vienna Convention on the Law of Treaties, Somalia is obligated not to take any action that would “defeat the object and purpose” of the treaty prior to its entry into force.

Under the Kampala Convention, the government is obliged to protect displaced people against forcible return to or resettlement in any place where “their life, safety, liberty or health could be at risk.” The state is also expected to consult with internally displaced people, allow them to participate in decisions relating to their protection and assistance, and allow them to make free and informed choices on whether to return, relocate, or locally integrate.

Under international law, the permanent or temporary removal of individuals, families, or communities against their will from the homes or land they occupy without providing access to appropriate legal or other protection is considered a forced eviction.

Somalia’s December 2014 policy on displacement requires the authorities to protect affected communities during evictions and lays out procedures largely in line with international law. The Interior Ministry and other authorities should implement the new policy in close consultation with displaced people; governmental, nongovernmental, and inter-governmental organizations; and in accordance with the UN Guiding Principles on Internal Displacement, Human Rights Watch said.

Before further evictions are carried out, the government, the UN, and aid agencies should also carry out a profiling exercise without undue delay to determine people’s needs. This should include identifying the most vulnerable people – such as female-headed households, unaccompanied children, the elderly, and the disabled.

Source: HRW