In September 1952, the last man to be hanged at Cardiff went to the gallows.

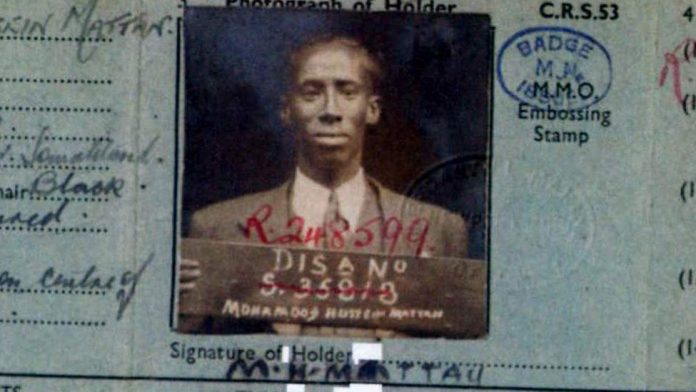

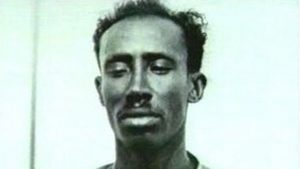

Mahmood Mattan was wrongly found guilty for the murder of shopkeeper Lily Volpert in Cardiff’s Tiger Bay.

It was to prove one of the most notorious miscarriages of justice in British legal history and went some way to hastening the abolition of capital punishment in the UK.

Now, a novel inspired by his story has been longlisted for the Booker Prize.

Mr Mattan was posthumously acquitted in 1998 – 46 years after he was executed – when it was found evidence had been largely fabricated and manipulated by police at the time.

Somali-born author Nadifa Mohamed said her motive for writing the semi-fictionalised The Fortune Men was to portray the real Mahmood Mattan.

“Previously, he’s been cast as this almost passive victim of police brutality, but there was far more to his character than that,” she said.

“People who knew him said he was spikey, brave, happy to stand up for his rights and for those of the people around him.

“I believe that is, in part, why the police had singled him out to take the blame for the next major crime to be committed in the area.”

Both born in what is now Somaliland, Mohamed’s father met Mahmood when the two emigrated to Hull.

“They were both in the Merchant Navy, but their lives took very different directions. My father said Mahmood was just an ordinary guy, albeit a bit of a loner,” she said.

A merchant seaman, Mahmood Mattan married paper factory worker Laura Williams in 1946 after settling in Tiger Bay, and the pair had three children together.

However, by 1950, the couple had separated and were co-parenting and living in the same street.

Mahmood was largely ostracised from the Somali community after being accused of stealing money from the Tiger Bay mosque, but when he was charged with murder they rallied around to pay for his legal defence.

On the evening of 6 March 1952, moneylender Lily Volpert, 42, had just closed her outfitters shop and was preparing to have supper, when there was a knock on the door.

Her niece saw her talking to a man at the entrance, but nobody could identify him. A few minutes later she was found with her throat cut, and around £100 was missing from the till.

The last two customers in the shop, Mary Tolley and Margaret Bush, said they had not seen anyone matching Mahmood’s description loitering but, after pressurised questioning, Mary Tolley changed her story, only to change it back again at trial.

A search of Mahmood’s house produced no evidence, yet he was arrested on the strength of the testimony of a Harold Cover, who was known to have a history of violence.

Other statements disproving Mahmood had been in the area were suppressed by the police in court; though his defence was hardly aided by his own barrister who, in summing up, described Mahmood as: “Half child of nature, half semi-civilised savage”.

Mohamed said her attitude to writing The Fortune Men had disturbing parallels with the police’s own approach.

“I opted for semi-fiction because I wanted to convey the atmosphere of the time in a way I didn’t think I could do with a straight-forward biography,” she said.

“It opens with a family all gathered around the radio to listen to the news of George VI’s death, a month before the murder.

“Yet the more I got into fictionalising the story, the more I realised that I was doing exactly what the police had done, I almost got into their mindset.

“It goes to show just how easily you can create a totally different version of events if you only look at what you’re prepared to see.”

Two events would cast doubt on Mahmood’s conviction.

In 1954, Tahir Gass, another Somali man investigated for Lily’s murder, was convicted of killing wages clerk Granville Jenkins in a country lane near Newport.

Then 15 years later, in 1969, Harold Cover, the man whose evidence had sent Mahmood to his death, was convicted of the attempted murder of his own daughter, by cutting her throat in precisely the same fashion as Lily had been killed.

Yet the Home Secretary James Callaghan refused to reopen the case.

“There really is no happy ending to this story,” Mohamed said.

“Laura believed in Mahmood’s innocence until the last but after his execution the family were moved to Ely and they never recovered; sinking into a life of poverty and despair.

“If there is any crumb of comfort, it’s that Laura lived long enough to see Mahmood’s conviction overturned by the Criminal Cases Review Commission in 1998 – the first case to be quashed by the organisation.”

The Booker committee will decide if The Fortune Men has been shortlisted in September, with the prize being awarded in November.

Source: BBC